Veritas

Table of Contents

- What is Veritas

- What does it do

- But what does using Veritas look like?

- Running the test code

- How and why did I make use of multi-threading

- Detecting test methods and invoking them

- Creating the pipeline

- The future

- Closing

What is Veritas

Veritas is a small testing framework that I am building for a friend's compiler. He started working on this project recently and seeing as how I found it very interesting, I decided to contribute to it. I then remembered that I do not know how to build compilers so I instead decided to finally look into things like reflection and frameworks and decided to build one for his language.

All cool projects have 2 things in common: a pipeline badge and a mythological name, so I made a pipeline and found out that the Romans had a goddess of truth called Veritas, somehow the Romans did not have a goddess of Unit Testing Frameworks so I unfortunately had to go with that.

What does it do

The fact that building a framework that is written in one language and tests another one is complicated should not be a surprise.

I essentially had to come up with a way of representing Po# code (that's what my friend called the language) as well as compiling, executing it and validating its output. I also wanted to make working with it not too different from commonly used frameworks as in I wanted everything to work through annotations, the tester should not have to worry about what was happening behind the scenes for the tests to work.

But what does using Veritas look like?

I am glad you asked! Here's an example:

@Test

class TestExample {

def valTest1(): (Boolean, String) =

"""def main(): int {

val a = 5;

print(a);

return 0;

}"""

.ShouldBe("5")

.Run()

}

If the code seems weird to you then worry not for there are docs about it.

I am not sure if this is a common thing under other languages or maybe under a different name but I have been doing a lot of C# lately and there is this concept of "fluent" syntax which essentially is code that is very intuitive and easy to read, almost like reading plain English. I was heavily inspired by Fluent Assertions and I want to add/change some stuff on the Veritas interface to make it a little more like it as I really like using it, I believe you can already see that it heavily inspired Veritas' design.

At this point, you might have noticed the interesting return type, a boolean string tuple? The boolean indicates whether the test passed or failed while the string holds a message useful for debugging (so if a test fails, it can show the difference between expected and actual value). I believe that because of how my test invocation works I cannot get the return value of the code directly, hence this ugly tuple, it's been some time since I "designed" this.

As I mentioned earlier, runtime exceptions aren't fully implemented into the language yet but when it comes to compiler exceptions you can do the following.

def parseErrorTest(): (Boolean, String) =

"{def a; a = 5; print(a);}"

.ShouldThrow(new ParseException(""))

Something similar will be added for runtime exceptions with possibly a .WithMessage option to verify that the code crashed with the

appropriate message but that will depend on how concise those messages end up being. The compiler error messages are a bit too

dev-debug friendly rather than language-user friendly for the time being so .WithMessage does not make sense for compile-time errors,

they essentially look like a small stack trace.

Another thing that is perhaps worth mentioning is the use of extension methods. Extension methods, in essence, add methods to a class from outside of this class. That sounds terribly boring until you realize how useful it is in some scenarios, in this case, it just looks a bit cleaner. Using extension methods I could ditch the old syntax of the tests that looked like this

def parseErrorTest(): (Boolean, String) =

new PoSharpScript("{def a; a = 5; print(a);}")

.ShouldThrow(new ParseException(""))

and instead go away with the class instantiation. I attached a few methods to the Scala String class which in turn call PoSharpScript

under the hood.

Scala implements extension methods through implicit classes;

implicit class PoSharpImplicit(val code: String) extends IPoSharp {

def ShouldBe(expected: String): PoSharpScript =

PoSharpScript(code).ShouldBe(expected)

def ShouldThrow(expected: Throwable): (Boolean, String) =

PoSharpScript(code).ShouldThrow(expected)

}

IPoSharp is a trait (or interface) that defines the 2 methods you can see below and PoSharpScript is the main class I use to interact

with Po# code. I made use of this recently as a wrapper to the PoSharpScript class since the logic was already implemented there,

this is purely for syntactic sugar.

Running the test code

This part is a little messy. Compiling and writing the assembly code to a file is easy since there are methods for this in the main package of the compiler but I also have to run it somehow. In case you haven't checked out the repo, you need WSL to run the code, you cannot run some of the tools natively on windows. Thankfully, Scala has this Process class that can help with that. I can use that class to spawn an external process that launches WSL and runs MAKE

import scala.sys.process.Process

Process(s"wsl make TARGET_FILE=$fileName").!!

This snippet returns anything that would normally get printed to the terminal if we were to run this command. TARGET_FILE is a variable

used in the makefile to specify the .asm file as well as the executable.

How and why did I make use of multi-threading

The way the compiler works is: it gets fed some input in Po# from either a .txt file or in this case just a string, that gets parsed

and compiled to NASM which gets dumped to a .asm file which we can now finally execute. That's cool but how can

we actually get the test output then? Well, there doesn't seem to be a good solution to this, or at least not one that I could come up with.

What I settled for is reading the last thing that the code prints which of course requires the snippet to print something. As of now,

runtime exceptions have not been fully added yet but when that happens, the same would apply for getting the exception message and I could

additionally check the exit code.

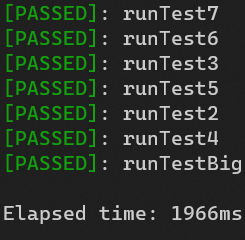

Executing the test snippets is terribly slow because of all the file accesses + compilation required + spawning the external WSL process. At the time of writing this, 7 tests executed sequentially take 5-6 seconds, this will only get worse with more tests. Since there are only so many tests as of now we can afford to assign one test per thread (which seems to be the most efficient for the time being), that takes the execution time down to around a second or two, this will hopefully scale much better than the sequential solution.

Since a .asm file gets created for each test I need to make sure that they have unique names so the different threads don't cause issues.

I decided to set the file name to packageName.className.methodName which should be unique at all times. These are also cleared after

all tests are finished executing so no artifacts are left behind.

I tried to think a bit ahead here and try to find out what would be a good future-proof optimization to make. Up until this point, spawning one thread per test is the most efficient way of running the tests which if you've done multi-threading may sound overkill and or counterintuitive but again, the process of running a test is very slow. But since it's probably not a good idea to allocate threads in this way for 1000 tests I decided to allow for chunking the test methods per thread which should be the best of both worlds; it is not fully sequential so we have a performance boost but it also scales better since each thread will be handling more than one test at a time. This should in theory be faster in the future when more tests get added compared to having a set amount of available threads with one test each and having to wait for them to finish running before you allocate another one for the next test. Since it is still early and I can't know what the optimal amount of threads or number of chunks is both are variables.

Detecting test methods and invoking them

I settled with the following:

- All test classes must be in the

testpackage - All test methods must be defined inside of a class annotated with

@Test - All test methods must include the keyword

testin their name

I kind of combined what JUnit and PyTest do with the @Test and method names (although

I think PyTest does it with filenames instead of method names). I could've made it so you need the methods annotated instead but decided to

go for this instead for no particular reason other than it will look a bit less cluttered. Since I consider tests to have test in their

method name one can also easily define helper methods in the class and they won't be treated as tests.

I found this a great library that allows you to easily use reflection.

I first need to get all classes inside the test package which I achieve with the following:

import org.reflections.Reflections

import org.reflections.scanners.Scanners.TypesAnnotated

import org.reflections.util.ConfigurationBuilder

val reflections = new Reflections(new ConfigurationBuilder()

.forPackage("test")

.setScanners(TypesAnnotated))

I then take the results of that query and extract the class names from the package. At this point, the class names

should look something like test.className.

reflections

.getStore

.get("TypesAnnotated")

.get("scala.reflect.ScalaSignature")

.toArray

.filter(_.asInstanceOf[String].contains("test."))

.map(_.asInstanceOf[String])

Here's where the more interesting things happen. We need to first get the class and then also create an instance for it

val testClass = ScalaClassLoader(getClass.getClassLoader).tryToInitializeClass(c)

val instance = ScalaClassLoader(getClass.getClassLoader).create(c)

This may be a little confusing but the two are different; testClass is essentially a reference to the test class. This later

allows us to use getMethods to find the tests inside of it which, in order to run, we need to instantiate it first hence the

instance. I made a separate method for executing the test since the code was getting a little cluttered. This just invokes the

method and based on the return value, it prints whether the test passed or not.

def runTest(instance: AnyRef, el: Method) = {

// Catches invalid tests (say main is missing from the code snippet)

try {

lastMethodName = el.getName

val (output, actual) = el.invoke(instance).asInstanceOf[(Boolean, String)]

if (output) {

// print passed

} else {

// print failed

exitCode = 1

}

} catch {

case e: Exception =>

// print error

exitCode = 1

}

}

This is a little bit simplified compared to the actual method; I wanted to be able to run this method from different threads

so I had to use a synchronized StringBuilder for the outputs. In order to not lock it too often, I chunk the results to a

temporary StringBuiler and only push them to the synchronized one once the thread is done executing its tests.

- Was this necessary? No

- Does it give any significant performance increase? Not really

- Is it cool that I did it regardless? Yeah 😎

On the topic of cool things, Scala has this library which makes it easy for you to use ANSI escape sequences and add some color to your prints!

Creating the pipeline

Building the pipeline was more complicated than it sounds. For starters, the project initially used SBT. When I was developing the framework I would test run it using Intellij which would compile everything with Java behind the scenes unlike SBT which uses Scala. Turns out the 2 have some runtime differences when it comes to the classloaders and the test classes could not be detected so I eventually made a merge request that made everything work through Gradle which took a bit of fiddling around until everything started working again but at least the classloaders were not complaining anymore.

Another issue I had was getting the pipeline to work on an Ubuntu image which seemed to also have some classloader issues because the test methods could not get invoked. In case anyone is willing to take a look and potentially fix it, here's the pipeline run and the pipeline yml file.

Other than that small hiccup, the rest was fairly standard stuff.

I want the pipeline to run on master pushes and on pull requests. The job should run on a windows image, I checkout to the repo and use this action to set up WSL, Gradle has a short post about setting up a Gradle build workflow here which I used for the setup and finally I install any WSL dependencies I need and run the Gradle task for the tests

name: Build and Test

on:

push:

branches:

- "master"

pull_request:

jobs:

gradle:

runs-on: windows-2022

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v2

- name: Set up WSL

uses: Vampire/setup-wsl@v1

- uses: actions/setup-java@v2

with:

distribution: temurin

java-version: 17

- name: Setup Gradle

uses: gradle/gradle-build-action@v2

with:

gradle-version: 7.3

- name: Execute Gradle build

run: gradle build

- name: Install dependencies

shell: wsl-bash {0}

run: |

apt update

apt install make nasm gcc -y

- name: Run tests

run: gradle runTests

About a month and a half had passed since I started working on Veritas before I finally saw this

and this

The future

As I mentioned earlier, the framework is not done which is to be expected since the language itself is not done evolving. Now that the the pipeline is also complete I have reached a point where the framework is both capable enough to test anything currently present in the language and can ensure that nothing breaks over time through the pipeline.

That being said, I now have the freedom to worry about more "trivial" things such as

- Actual error handling that does not simply wrap the entire framework in a try-catch

- Improved error messages for anything that could go wrong

Stealget inspiration from Fluent Assertions on new things to add

Of course, this is what I can come up with now, more stuff will probably appear along the way as the language evolves.

Closing

All in all, it has been really cool and interesting to work on this. It was really interesting to dive into reflection, it really is fascinating to me how you can interact with a project's source code through ... more source code. It also gives you a better understanding of how these frameworks function which is great. Multi-threading was another thing I enjoyed getting into, I recently developed an interest to parallel programming and this is one of the ways I pursued that interest. It's nice knowing your code helps someone and makes their lives easier but also more boring because who likes writing tests am I right?

Really interested in seeing where this will go from now, till next time!